Native Americans, trappers, and stalwart pioneers knew about the Yellowstone region’s amazing geysers, hot springs, rivers, bison herds, and bears long before Yellowstone became a national park.

But in 1870, Wyoming was a territory and Yellowstone’s marvels were a mystery to Congress and most of the U.S. population.

Back then — long before selfies, digital images, and Instagram — artists depicted the world’s wonders for a curious public. And in the case of Yellowstone, the photographers, illustrators, and painters who portrayed the area proved instrumental in its establishment as a national park. Three such artists — Thomas Moran, William Henry Jackson, and Frank J. Haynes — played a seminal role in Yellowstone’s preservation.

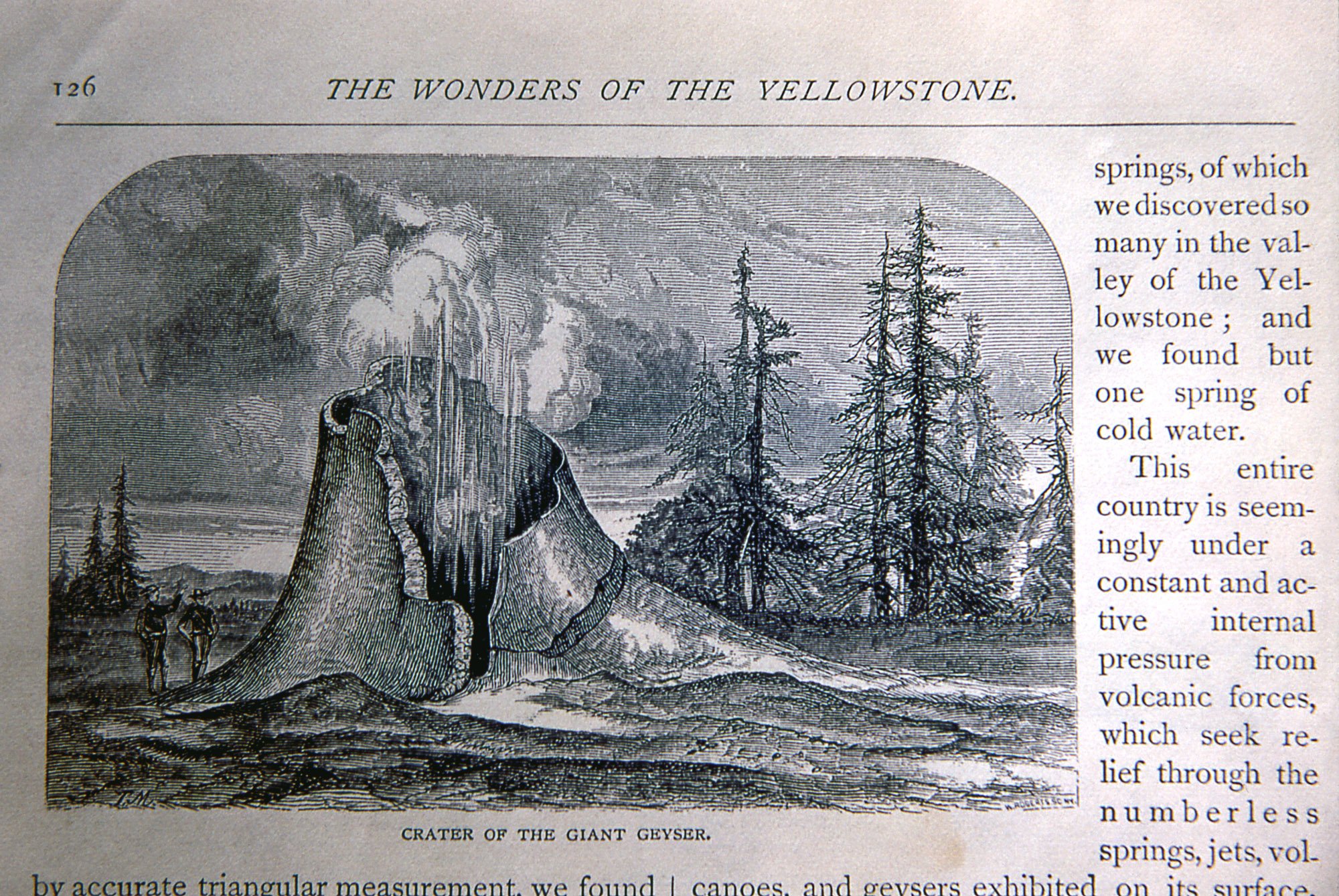

An illustrator and painter, Moran’s first depictions of Yellowstone were second-hand. He improved upon rough sketches of geysers and hot springs created by explorers for publication in the June 1871 issue of Scribner’s Monthly.

It was through his association with Scribner’s that he first learned of the Hayden Expedition. He agreed to join the expedition at his own expense, and with the support of Jay Cooke and Company, owners of the Northern Pacific Railroad, Moran was welcomed as a member of the survey team. The Northern Pacific Railroad had a vested interest in Moran, as they were looking to popularize the area in the interest of expanding their railroad westward.[1]

Photographer William Henry Jackson and Moran joined Ferdinand Hayden’s 1871 expedition to survey the Yellowstone region for the federal government. William H. Jackson accompanied the expedition to photograph Yellowstone and Thomas Moran came along to paint what he saw. Jackson and Moran documented more than 30 different sites, including Old Faithful and the tumbling Lower Falls of the Yellowstone River.

To convince Congress to make Yellowstone the first national park, Hayden, then director of the U.S. Geological Survey, showed senators, representatives, and President Ulysses S. Grant the works of Moran and Jackson. The beauty they captured through photographs and paintings helped inspire members of Congress, who had never seen the area. The watercolors, illustrations, and photographs depicting Yellowstone’s scale and grandeur did more than written or oral descriptions to persuade Congress to preserve the area. On March 1, 1872, Grant signed the bill to make Yellowstone the first national park.

While Moran’s impact on Yellowstone was significant, Yellowstone had a major influence on the artist, too. His national reputation as an artist became intricately tied to Yellowstone. He even adopted a new signature — T-Y-M, Thomas “Yellowstone” Moran — and the North Rim overlook from which he painted was named for him, Moran Point.

Moran’s watercolors beautifully portray Yellowstone’s remarkable scenery and grandeur. But at times even Moran was overwhelmed by its display of beauty. It is said that when he first gazed upon the canyon known now as the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, he remarked that its beautiful colors “were beyond the reach of human art.” Nonetheless he proceeded to record the scene as best he could with his watercolors, just as Jackson recorded what he saw with his camera.[2]

In April 1872 Moran completed his signature version of the lower falls, the massive “The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone,” which caught the imagination of the country. Today, the original painting, 7 feet high by 12 feet wide, hangs in the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C.

To learn more Thomas Moran, click here to read the transcription of his diary.

Jackson’s career, too, became intertwined with Yellowstone and the geology of the West. As official photographer for Hayden’s 1871 survey, Jackson was the first to capture photographs of legendary landmarks of the West, despite extremely challenging conditions. His photos provided conclusive evidence of Yellowstone’s majesty and drama, which until then, had been considered mythical exaggeration. Over a long career, he produced 80,000 images of the American West and was honored by having Mount Jackson, in the Madison Canyon area, named after him.

Another photographer, Frank J. Haynes, known as F. Jay Haynes, opened the first of several photography shops in Yellowstone at Mammoth Hot Springs in 1884. To shoot the first winter photos of Yellowstone, Haynes, along with arctic explorer Frederick Schwatka as well as sled dogs to pull their gear, set out in January 1887 on a 200-mile ski and snowshoe trip. Haynes returned with more than 40 images.

Considered the official photographer of Yellowstone National Park, Haynes successfully produced and sold his Yellowstone photographs. Beginning in 1899, he also created postcards with hand-tinted images of Yellowstone on one side and space for visitors to write a message on the other. Haynes’ son, Jack Ellis Haynes, who took over the family business in 1916, continued the postcard production until his death in 1962. Experts estimate that from 1900 to 1962 Frank and Jack Haynes published more than 55 million Yellowstone National Park postcards. Mailed within the U.S. and internationally, the postcards showcased Yellowstone to the world. Frank Haynes’ legacy lives on in Mount Haynes, a peak in the Madison Canyon area of the park, which was named for him.

Check out how contemporary artists are still being Inspired by Yellowstone.

Long-time family travel guru Candyce H. Stapen writes for many publications and outlets. She has written 30 travel guidebooks, including two for National Geographic, and her blogs and articles appear in many outlets. For more information, see gfvac.com and follow her @familyitrips.

For more travel experiences to Beautiful Places on Earth™ available from Xanterra Travel Collection® and its affiliated properties, visit xanterra.com/explore.

[1] https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/historyculture/thomasmoransdiary.htm

[2] https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/education/classrooms/painting.htm